Introduction

Vaccines have been used for many decades around the world and have significantly reduced the prevalence of disease by preventing many infectious and contagious diseases such as polio and smallpox. In the present day, vaccine research and development continue to play a critical role in our current healthcare system and help to combat infectious diseases such as shingles, influenza, and COVID-19.

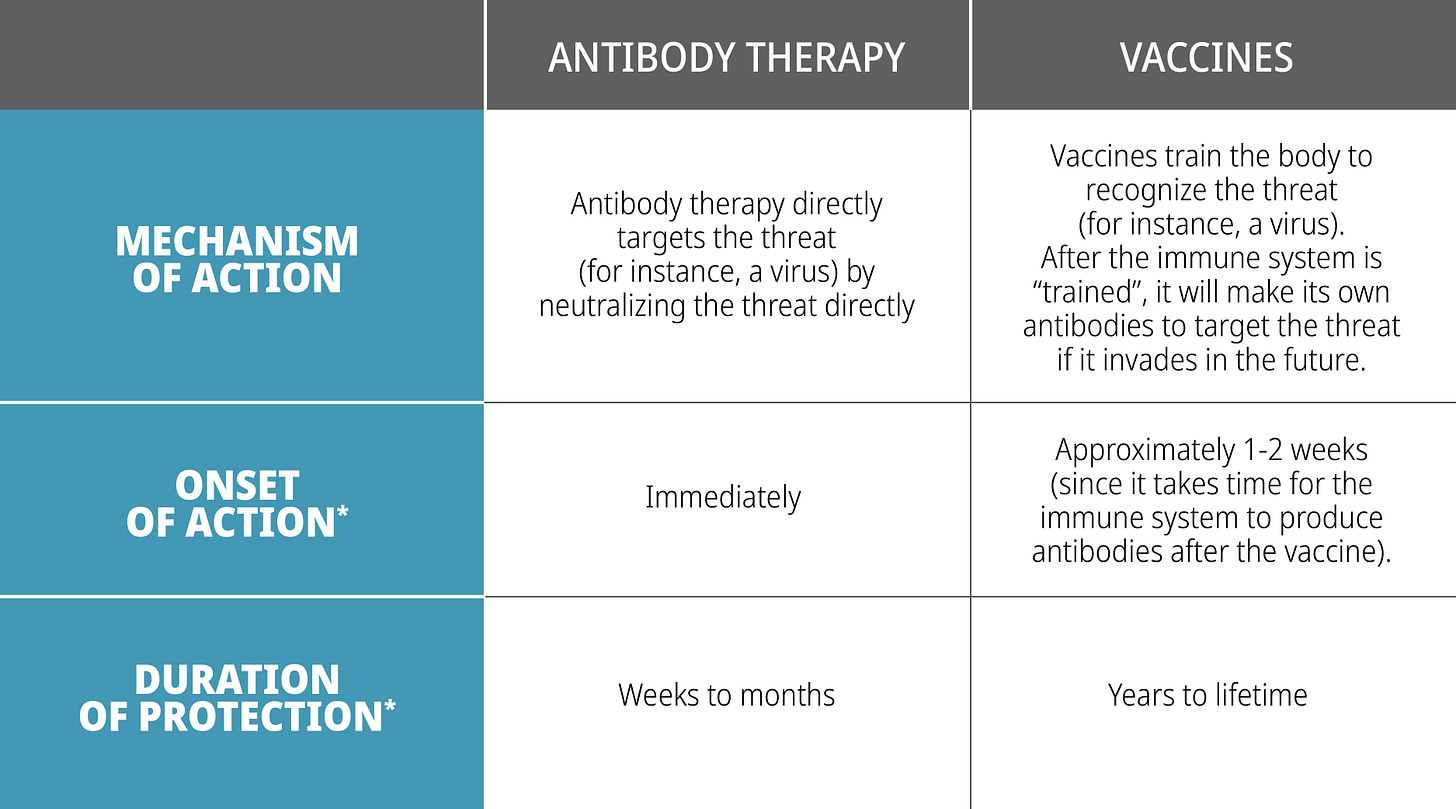

However, vaccines do have their disadvantages. For instance, vaccines can take 1-2 weeks to work, leaving a window of opportunity for infection. Additionally, since vaccines work by challenging one's immune system, there may be patients (e.g., those who are immunocompromised) that may not be capable of producing antibodies to fight off the infection. This means vaccines might not be effective and/or suitable to all patient populations.

These disadvantages are why monoclonal antibody therapy is a hot research topic. Monoclonal antibody therapy has a unique mechanism of action that can be used to prevent and/or treat diseases in a precise manner, filling a void left by the potential disadvantages inherent with vaccines. In this article, we will discuss the difference between monoclonal antibody therapy and vaccines.

But first, let’s start off with the basics:

What are vaccines?

There are several types of vaccines: inactivated vaccines, live-attenuated vaccines, mRNA vaccines and many more.

Although they are made with different components (e.g., inactivated vaccine contains inactive parts of the pathogen whereas live-attenuated contains a weakened version of the pathogen), they all share the same purpose, which is to teach our immune system how to fight off an infection.

When a vaccine is administered, it triggers the immune system to respond and produce antibodies that specifically counter the pathogen that causes the disease. Thus, if the patient is ever exposed to the actual pathogen, the body already has the antibodies prepared to fight off the infection.

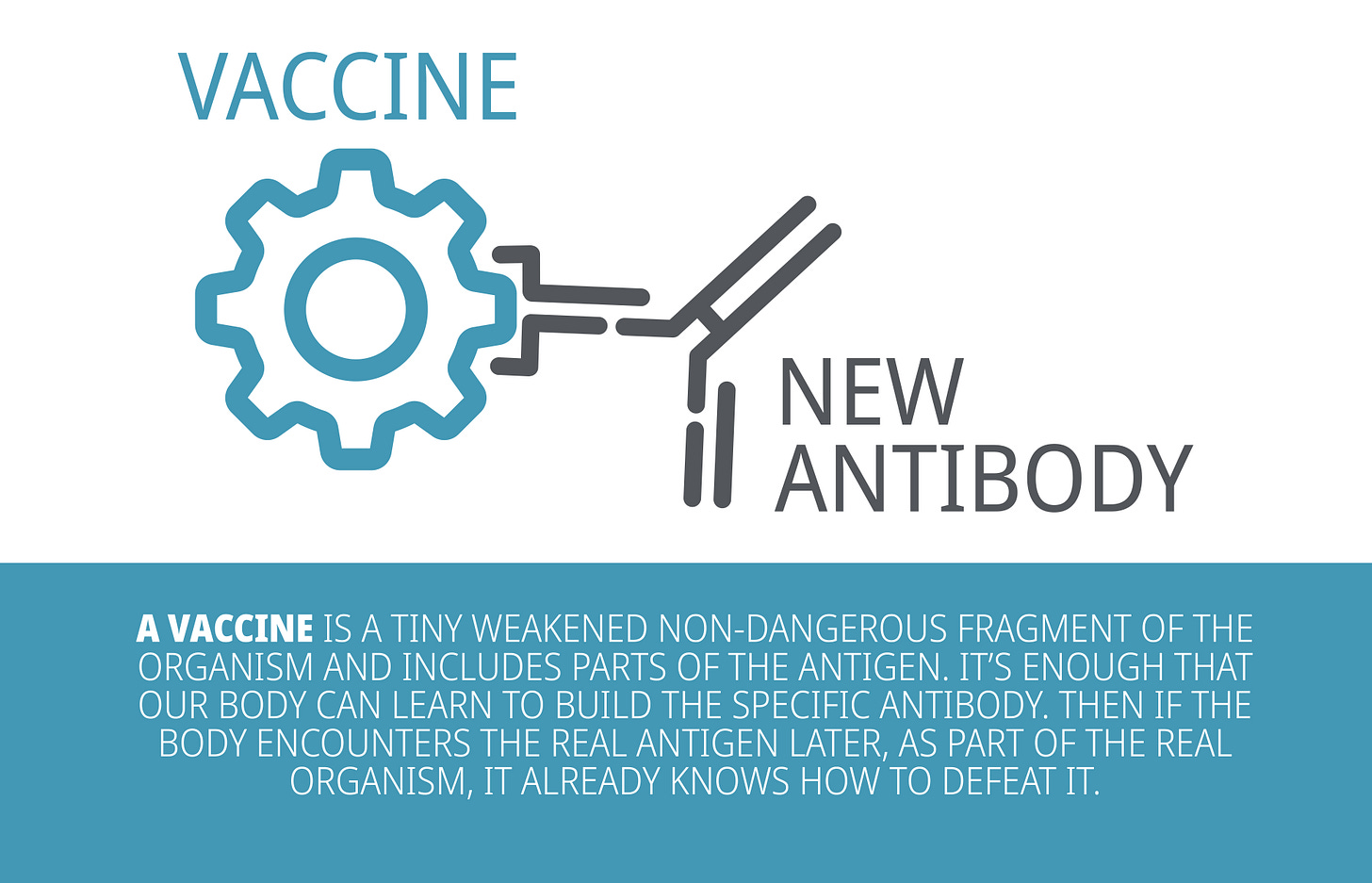

What are monoclonal antibodies?

Breaking down the terminology:

Monoclonal - Mono- means one, and clonal means clone, so it means that the antibodies are made from identical cells, making the antibodies all identical in that they bind to the same epitope (which is a part of an antigen molecule to which an antibody attaches itself). This contrasts with polyclonal, where antibodies are made from many cells, meaning the resulting antibodies are mixed and target different epitopes.

Antibodies - As you have learned from our previous articles, antibodies are a type of protein produced by our immune system in response to foreign invaders/threats (For a refresher, please refer to Deep Dive into Antibodies.

Therefore, when we combine these two words together, monoclonal antibodies are a collection of antibodies that are identical in nature, e.g., clones of the same antibody targeting the same epitope.

A recombinant monoclonal antibody is a molecule developed in a laboratory that is designed to mimic or enhance the body’s natural immune system response against threats, such as cancer or an infection.

For instance, when developing a monoclonal antibody to target an antigen, white blood cells (specifically, B cells) are exposed to the antigen (usually a protein). B cells which possess an antibody on the cell surface that is specific for the antigen present then activate and divide, resulting in clones of each B cell that ‘recognized’ the antigen using antibodies on their cell surface. To isolate a particular antibody of interest, millions of B cells can be separated into individual cells for screening. Researchers can determine if each individual B cell is in fact producing an antibody that successfully recognizes the antigen. Once determined, the genetic sequence encoding for the antibody is extracted, decoded, and used to produce large batches of the identical antibodies in the laboratory. This sample of a monoclonal antibody can then be used to test the strength of binding to the antigen and how the antibody may help treat or cure a disease.

Monoclonal antibodies can then be injected into patient, often intravenously (through the vein) where they bind to the target antigen when it is present in the human (often on the surface of a virus or bacterium) and initiate a cascade of events to help clear an infection (refer to Figure 1 below for an example of antibody binding to SARS-CoV-2).

What are the differences between antibody therapy vs vaccines?

Why are monoclonal antibodies important?

Monoclonal antibody therapies have several advantages to them:

Precision:

Monoclonal antibodies are molecules that bind specifically to their target. A targeted therapy allows for a more precise and efficient treatment, which can maximize efficacy while minimizing unwanted side effects. This would be in comparison to general and broad-spectrum therapies that are less specific.Example: Chemotherapy drugs often target and kill fast-growing cells because cancer cells tend to be fast-growing. However, this broad range of action affects other fast-growing healthy cells too (e.g., stomach cells). Damage to healthy cells can then cause unwanted side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting). Thus, there is a strong research focus on developing monoclonal antibody therapies with more specificity so that the drug action can focus and target cancer cells and minimize the effect on healthy cells.

Quick Onset:

Vaccination is not instantly effective. It can take several weeks to generate an immune response. In the interim, monoclonal antibodies can play a critical role to complement vaccines by providing immediate protection while the body generates an immune response. In this instance, it could help neutralize the targeted invader (e.g., virus) that may already be replicating rapidly in the patient's body.

Example: When someone is bitten by an animal with suspected rabies, they are often given both rabies immune globulin (RabIg) along with the rabies vaccine. Rabies vaccine provides a long duration of protection against the rabies virus while the rabies immune globulin (composed of antibodies) provides short (but instantaneous) protection until the patient builds an immune response from the rabies vaccine.

An alternative option when patients do not meet a vaccine eligibility:

Vaccines work by challenging and training one's immune system. There are cases where a patient may not meet the qualification criteria to obtain a vaccine for safety reasons (e.g., allergies, contraindications) or they may not have an adequate immune system (e.g., immunocompromised, elderly, pre-existing conditions) to produce antibodies to fight off the infection.

Hence, monoclonal antibody therapy plays an important role in these patient populations because this means we can directly give and supply the antibodies required to help protect these patients from infection.

A potential solution when there are no vaccines available:

Vaccine development is inherently challenging. Some challenges include selecting suitable animal model for testing, high rates of mutations in some viruses, and the risk of vaccine-associated enhanced diseases (VAED). Due to these challenges, the development of vaccines for some diseases have been halted or delayed. To address this gap, monoclonal antibody can be an alternative solution.

Example: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is one of the leading causes of serious respiratory diseases in young children. However, there are currently no approved vaccines available. There are several challenges in developing an RSV vaccine, including the lack of appropriate animal models and the risk of VAED (a previous attempt to develop a RSV vaccine in 1960 had resulted in enhanced respiratory disease in patients).

Due to the significant health impact, there is ongoing research for a suitable RSV vaccine. Currently, there are many RSV vaccine candidates in development, but it will take some time before they can reach the drug market as an approved vaccine. In the meantime, the only approved medication against RSV infection is palivizumab. Palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody, is indicated for the prevention of serious lower respiratory disease caused by RSV in high-risk pediatric patients.Prevent Mutation Escape:

Viruses have an ability to evolve and mutate to change their antigens. This evolution can pose a significant problem because it means our current vaccines and antibody therapies can become less effective.

If the virus mutates in a way that changes the antigen, this means the new mutated virus may not be recognized by the antibodies produced against the original version of the virus. This concept is called mutation escape. Thus, these viral mutants can escape detection, survive, and continue to replicate rapidly in the human body. This is a trending topic especially with the rise of COVID-19 variants.

Monoclonal antibody therapies can play a key role in addressing mutation escape because antibodies have flexible characteristics, which allows them to be designed and modified in the laboratory setting. Monoclonal antibodies can be modified and tested more rapidly than vaccines and can potentially address these mutants as they arise.

Researchers are currently focused on designing antibodies that can recognize escape mutants by designing a cocktail of antibodies that target different regions of the viral antigen to prevent the generation of antibody-escape mutant viruses. Theoretically, while a mutation may happen in one epitope of the virus (the region of the virus where the antibody binds), the virus would still be susceptible to one of the other antibodies that targets a different, non-mutated region of the virus.

Conclusion

As we can see, vaccines and antibody therapies both play a critical role in our healthcare system to prevent and treat many diseases. Monoclonal antibody therapy is a promising field of research that will fill many gaps in our current treatments and pave a new path to more effective therapies for infectious diseases, cancer, autoimmune diseases, and many more.

References

Baum et al. (2020). Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7299283/

Biagi et al. (2020). Current State and Challenges in Developing Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccines. Vaccines. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040672

Cohen, J. (2020). Designer antibodies could battle COVID-19 before vaccines arrive. Retrieved from https://www.science.org/content/article/designer-antibodies-could-battle-covid-19-vaccines-arrive

Coronavirus Prevention Network. (2021). Science of Vaccines and Monoclonal Antibodies. Retrieved from

https://www.coronaviruspreventionnetwork.org/coronavirus-vaccine-and-antibody-science

Golsaz-Shirazi et al. (2017). Construction of a hepatitis B virus neutralizing chimeric monoclonal antibody recognizing escape mutants of the viral surface antigen (HBsAg). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28641998/

HealthLink BC. (2018). Rabies Immune Globulin and Vaccine. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/healthlinkbc-files/rabies-immune-globulin-and-vaccine

Munoz et al. (2021). Vaccine-associated enhanced disease: Case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Retrieved from

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X21000943

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: September 17, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-september-17-2021

World Health Organization. (2020). How do vaccines work? Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/how-do-vaccines-work

Regarding; ''If the virus mutates in a way that changes the antigen, this means the new mutated virus may not be recognized by the antibodies produced against the original version of the virus'' Natural Immunity will take care of that...I wouldn't worry about too much.